The Morning That Keeps Repeating

You started this business because you're exceptional at something.

Maybe you're a contractor who can walk into a mess and see exactly what needs to happen. Maybe you're a consultant who can untangle problems that baffle your clients. Maybe you build things, fix things, design things, or solve things that other people can't.

And at some point, the phone started ringing. People wanted what you could do. So you hired someone. Then someone else. You got an office, or a shop, or a bigger truck. The business grew.

But something else grew with it.

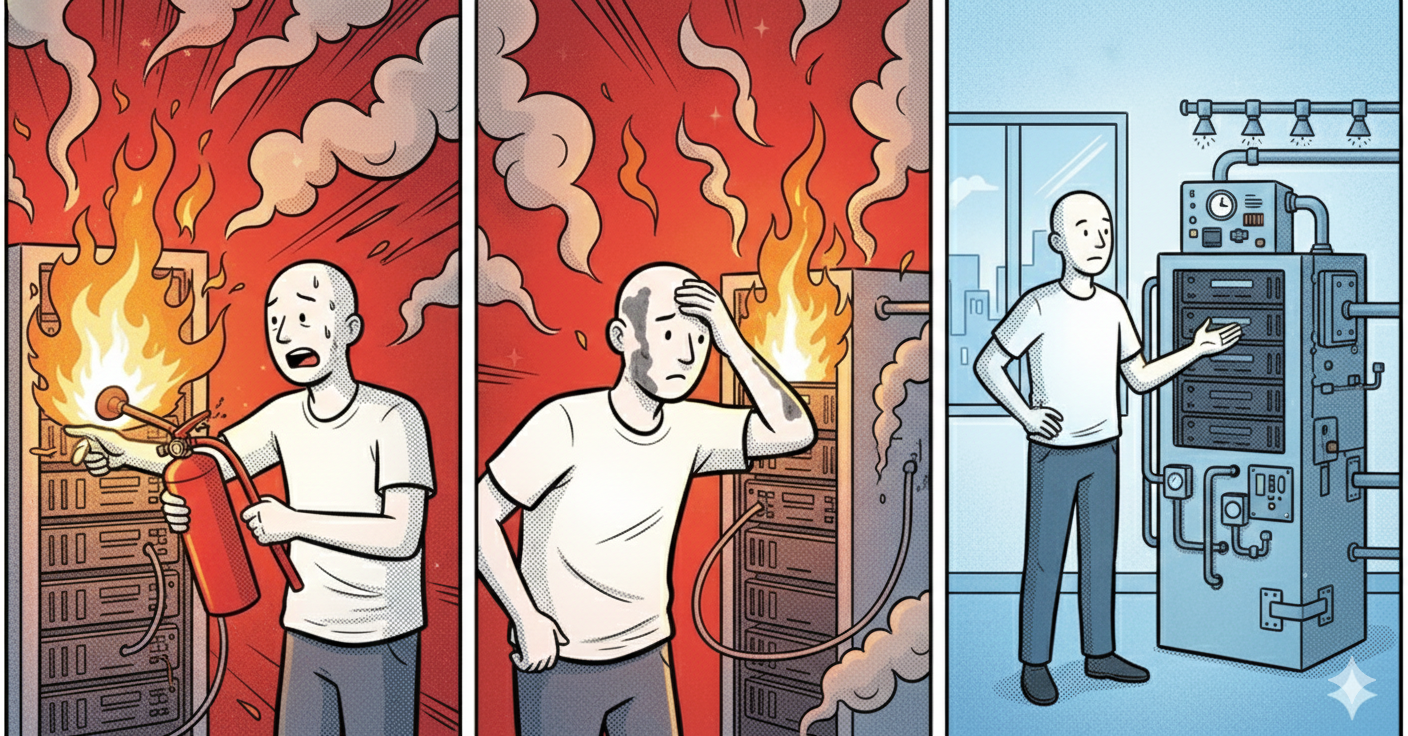

The fires.

Not literal fires—though some days it feels close. The customer who's furious because something fell through the cracks. The job that went sideways because the wrong materials showed up. The employee who quit without warning. The invoice that never got sent. The callback that should have been unnecessary. The miscommunication that cost you a week.

You put one out. Then another. Then another.

And then you notice: you're not practicing your craft anymore. You're just fighting fires.

The Cost Nobody Talks About

Here's what these fires actually cost you:

Time—the hours you spend untangling problems that shouldn't have happened. The evenings reviewing work that should have been right the first time. The weekends catching up because the week was consumed by crises.

Money—the jobs you have to redo at no charge. The discounts you give to keep angry customers. The overtime you pay because nothing went according to plan. The opportunities you miss because you're too buried to pursue them.

People—the good employees who leave because they're tired of the chaos. The new hires who never get properly trained because there's always an emergency. The team that burns out because every day feels like survival mode.

And the hardest cost to quantify: the thing you actually love doing—the craft that started all of this—gets squeezed into whatever space is left after the fires are handled. Which, most days, isn't much.

You didn't start this business to become a full-time firefighter.

But somehow, that's what happened.

Why the Fires Keep Coming Back

Here's what most business owners don't realize:

The fires feel like random bad luck. This customer was difficult. That supplier dropped the ball. This employee made a mistake. That situation was unusual.

But if you step back and look at the pattern, you'll notice something:

The same types of fires keep happening.

Maybe it's always communication—customers who expected one thing and got another. Maybe it's always handoffs—work that falls through the cracks between people or phases. Maybe it's always quality—issues that get caught too late, or don't get caught at all.

Different specifics. Same underlying pattern.

And here's why they keep coming back:

You're fighting fires at the output. But fires are created at the input.

Every fire you're putting out today is the result of something that happened earlier—a decision that wasn't made clearly, a step that wasn't defined, a handoff that wasn't structured, an expectation that wasn't set.

The fire shows up at the end. But it was lit at the beginning.

Which means: as long as you're only fighting fires when they appear, you'll be fighting fires forever. You're treating symptoms. The cause is still upstream, still creating the next fire, still waiting to consume tomorrow's schedule.

The Craftsperson's Trap

There's a particular version of this problem that hits craftspeople harder than anyone.

You're excellent at your craft. You know the right way to do things. You can look at a piece of work and immediately see what's wrong with it. Your standards are high because they have to be—your reputation depends on it.

So when a fire happens, you know exactly how to fix it. You jump in. You solve it. You make it right.

And that's the trap.

Because you're so good at fixing problems, the business learns to depend on you fixing problems. Nothing forces the underlying issues to get solved. Why would it? You're always there to catch what falls.

Your competence becomes the system. Your heroics become the operating model.

And the business can never grow beyond your personal capacity to intervene. Every fire needs you. Every crisis requires your judgment. Every recovery depends on your effort.

The very thing that made you successful—your ability to make things right—becomes the thing that keeps the fires burning.

Everyone Wants to Be Superman

Think about what Superman actually does.

He shows up after the building is on fire. After the train jumps the tracks. After the disaster is already in motion. He's celebrated for the rescue—the dramatic, last-second intervention that saves the day.

But the rescue only exists because something already went wrong.

Superman is reactive. He's the ultimate firefighter. And if you're good at your craft—if you can swoop in and save situations that would sink other people—there's something intoxicating about being Superman. The gratitude. The indispensability. The proof, over and over, that you're the one who can make things right.

But there's a cost to being Superman.

Superman doesn't get to have a normal life. He's always on call. Always watching for the next disaster. The cape is never really off.

Now think about Clark Kent.

Clark is a journalist. He investigates. He asks questions. He understands systems—how power works, how institutions fail, how problems develop before they become crises. Nobody writes headlines about "Reporter Publishes Story That Prevents Disaster." But that's the work that actually changes outcomes.

Here's the thing most people miss about Superman:

Clark Kent isn't the disguise. Superman is.

Clark is who he chose to be. The life he actually wants to live. The quiet, deliberate work of understanding how things work and making them work better—that's the identity he built for himself.

Superman is what he gets pulled into when systems fail.

When you're running a business, you have the same choice. You can be Superman—always rescuing, always heroic, always exhausted. Or you can be Clark Kent—building systems designed to prevent fires, asking the questions, doing the unglamorous work that prevents disasters from happening in the first place. It's the difference between Cowboys and Surgeons—between those who thrive in chaos and those who eliminate it.

Everyone wants to be Superman.

But maybe you should consider being Clark Kent.

Output Thinking vs. Input Thinking

Most business owners spend their lives in output thinking: dealing with what's happening now, reacting to what just went wrong, fixing what's in front of them.

Output thinking asks: How do I put out this fire?

That's Superman thinking. Arrive at the disaster. Deploy your powers. Save the day.

But there's another way to think:

Input thinking asks: What created this fire in the first place? And how do I prevent that from happening again?

That's Clark Kent thinking. Investigate. Understand. Address the root cause.

When you think about inputs, you start to see things differently:

The angry customer isn't just an angry customer—they're evidence that expectations weren't set correctly at the start.

The quality issue isn't just a quality issue—it's evidence that there's no checkpoint where that would have been caught.

The missed deadline isn't just a missed deadline—it's evidence that the timeline was never realistic, or the dependencies were never mapped, or the handoffs were never defined.

Every fire is a signal. It's telling you something about your inputs. Something upstream is broken, unclear, or missing entirely.

The question isn't how to fight fires faster. The question is: what would have to be true for this fire to never start?

What "Solving It Once" Actually Means

Here's what input thinking looks like in practice:

The fire: A customer is upset because the final result didn't match what they expected.

Superman response: Apologize, redo the work, give a discount. Save the relationship through heroic effort.

Clark Kent response: Why didn't expectations match? Where was the disconnect? Was there a clear approval point? Did someone confirm the specs before work began? Was there a visual or document or conversation where both sides agreed on what "done" would look like? If not—that's the input problem. Not this customer. Not this job. The fact that work can start without confirmed expectations.

The fire: A team member made a mistake that cost you a callback.

Superman response: Talk to them about being more careful, fix the mistake yourself.

Clark Kent response: What would have caught this before the customer did? Is there a checkpoint? A second set of eyes? A quality standard that's documented somewhere, or does "quality" just mean "whatever the owner thinks it should be"? Does this person even know what the standard is? If the standard only exists in your head—that's the input problem.

The fire: A job went over budget because materials were wrong.

Superman response: Eat the cost, remember to double-check next time.

Clark Kent response: How do materials get specified? Who verifies them before ordering? Is there a checklist, or does it depend on someone remembering? What happens between the estimate and the purchase order that allowed wrong materials to get through? If "remembering" is the system—there is no system. That's the input problem.

The Shift

Making this shift—from output thinking to input thinking, from Superman to Clark Kent—requires something uncomfortable:

You have to stop being the hero.

The hero identity feels good. Being the one who can fix anything, save any situation, rescue any job. Being indispensable.

But the hero is also the bottleneck. The hero is why the business can't run without you. The hero is why vacations aren't really vacations. The hero is why growth feels like adding weight instead of building capacity.

The shift isn't about working harder or being smarter or hiring better people—though all of those might help. The shift is about redirecting your effort:

From fixing problems to preventing them.

From catching errors to eliminating the conditions that create them.

From being the system to building the system.

From Superman to Clark Kent.

This is harder than fighting fires. Fires are urgent and clear. Prevention is ambiguous and easy to postpone. There's always a reason to deal with what's burning now and worry about prevention later.

But "later" is how you end up years into a business that still depends on your heroic effort to survive every week.

Where to Start

If you've been fighting fires for years, the idea of "solving them at the input" can feel overwhelming. Where do you even begin?

Start with the fire that keeps repeating.

Not the one-off disaster. Not the freak occurrence. The one you've seen before. The one that makes you think, "Why does this keep happening?"

That's your signal. That's where something upstream is broken.

Ask yourself:

What happened right before this fire started?

What decision was made—or not made—that allowed this to happen?

What information was missing, unclear, or assumed?

What handoff failed, or never existed in the first place?

What checkpoint would have caught this earlier?

Then ask: What would have to be true for this fire to be impossible?

Not unlikely. Not rare. Impossible.

That's your input. That's what needs to be designed.

The Life You Actually Wanted

There's a version of your business where the fires don't keep coming back.

Not because nothing ever goes wrong—things will always go wrong. But because when they go wrong, there's a structure that catches them. There's a checkpoint that flags the issue before it becomes a crisis. There's a defined path that doesn't depend on you remembering, or intervening, or saving the day. A shared language that lets you and your team name where things break—and diagnose them stage by stage.

In that business, your craft gets room to breathe. Your best people can do their best work. Growth creates capacity instead of chaos.

And you can take a weekend—a real weekend—and come back to a business that ran without you.

That business isn't built by being a better Superman. It's built by being Clark Kent.

By doing the quiet, unglamorous, deliberate work of understanding how things fail—and designing them so they don't.

Clark Kent isn't the disguise. It's the life he actually chose. The identity he built on purpose. What would your business look like if you made the same choice?

Superman or Clark Kent?

The work is the same either way. The life you get to live while running this business is not.

Further Reading

- On systems thinking: Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing. The foundational text on understanding how system structures create outcomes—and why intervening at the input changes everything downstream.

- On the theory of constraints: Goldratt, E. M. (1984). The Goal. North River Press. A business novel that demonstrates how bottlenecks determine throughput—and why optimizing anywhere else is wasted effort.

- On building businesses that don't depend on heroics: For the complete framework on designing deliberate systems, Deliberate Work covers the methodology in depth. Get on the early access list.

Superman™ and Clark Kent™ are trademarks of DC Comics, a WarnerMedia company. References to these characters are used here for illustrative and commentary purposes only. This article is not affiliated with, sponsored by, or endorsed by DC Comics or WarnerMedia.