The Advice That Shaped a Generation

In July 2013, Paul Graham published an essay that became gospel for a generation of founders: "Do Things That Don't Scale."

His argument was elegant. Startups don't take off by themselves—founders make them take off. And the way you make them take off is by doing things that seem inefficient: manually recruiting users one by one, going overboard to make early customers happy, handling things by hand that you'll eventually need to automate.

He called out the Collison brothers at Stripe, who would say "Right then, give me your laptop" and set up new users on the spot. He talked about Airbnb founders going door to door in New York, taking photos of apartments themselves. He described the hands-on, high-touch, seemingly inefficient work that actually gets a company off the ground.

The advice was brilliant. And it was right.

But it was incomplete.

Because buried in the essay was an assumption that most founders heard but didn't fully internalize: the point of doing things that don't scale is to learn. And learning only becomes valuable if you capture it in a form that scales.

The Hidden Filter

Here's what I've observed over 25 years of building and watching businesses:

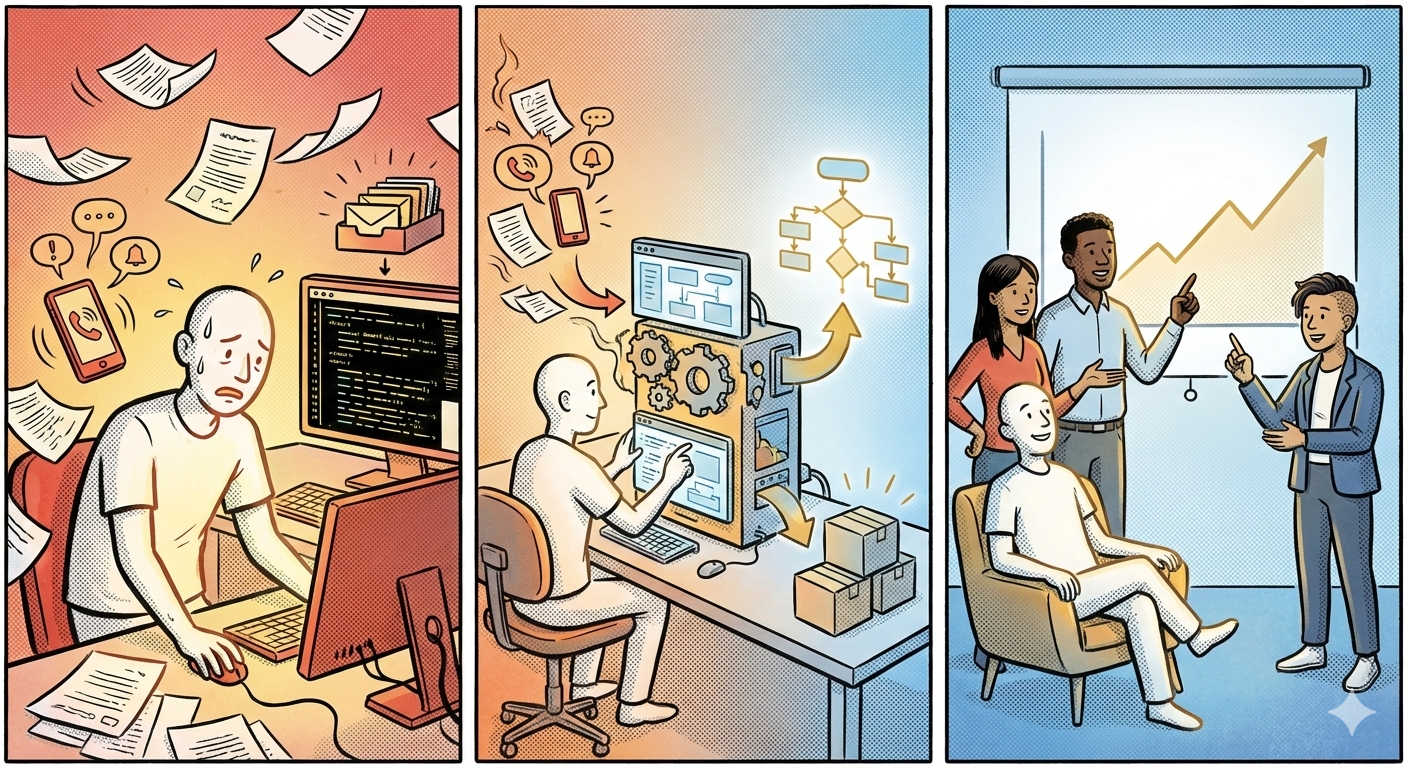

The difference between the companies that made it and the ones that flamed out wasn't just whether founders did things that didn't scale. Every early-stage company does unscalable things—they have no choice.

The difference was whether they could do two things simultaneously:

Figure out what actually matters—what customers want, what the market will bear, which problems are worth solving.

Turn what you learned into repeatable processes that don't depend on heroic effort or founder involvement.

Most founders heard "do things that don't scale" and focused entirely on the doing. They recruited users. They went overboard on service. They handled everything manually. They learned.

But the winners were doing something else at the same time: they were building systems as they learned. Every manual process was a draft of an eventual automated one. Every heroic save was data for designing a system that wouldn't need heroes—developing expertise and designing systems in parallel.

The Collison brothers didn't just install Stripe on people's laptops. They were learning exactly what the installation process needed to be—then building it into the product.

Why Most Companies Never Got There

If systematizing was always the goal, why did so few companies actually do it?

Because in 2013—and for years afterward—systematizing was slow. It required a completely different skillset than the doing itself. Founders who were great at the hands-on, high-touch, unscalable work were often terrible at abstracting their learning into process design.

Think about what "systematize" actually meant in practice:

→ Stop doing the thing long enough to document how you do the thing

→ Abstract your intuitive decisions into explicit rules

→ Design workflows that someone else could follow

→ Build or configure tools to support those workflows

→ Train people on the new system

→ Iterate when the system breaks

That's a massive investment of time and cognitive energy—exactly the resources early-stage founders don't have. So they kept doing. And doing. And doing.

The heroics became the system by default. The workarounds became permanent. The tribal knowledge stayed tribal.

They didn't scale the learning. They scaled the chaos.

And then they spent the next five years trying to unwind it—or they didn't, and wondered why growth was so painful.

What Changed

I'm not here to tell you Paul Graham was wrong. He wasn't. The advice was exactly right for the constraints of the time.

But the constraints have changed.

AI has fundamentally altered the economics of thinking through operational implications. The gap between "learning" and "systematizing" used to be measured in months. Now it can be measured in hours.

Consider what's now possible:

While you're doing the unscalable work

You can simultaneously design the workflow that will eventually replace it—mapping triggers, defining handoffs, specifying what "done" looks like at each stage.

While you're handling edge cases

You can capture them as decision rules, building an explicit system for handling the exceptions before they become folklore.

While you're learning what customers actually need

You can model how that learning translates into service delivery at 10x your current volume—before you get there.

The excuse for not designing the system—"we don't have time, we need to move"—is gone. You can move fast and think dimensionally. You can do things that don't scale and design for scale simultaneously.

"Do things that don't scale" and "design for scale" are no longer sequential. They're simultaneous.

The GTM Gap Nobody's Talking About

Here's something I've noticed while studying how GTM consultants and frameworks operate:

They're very good at the first thing—helping you learn the right things. ICP definition. Positioning. Problem articulation. Funnel stages. Metrics and cadences.

But almost universally, they stop at the same layer.

They give you maps, frameworks, and measurement systems. They help you understand what should happen at each stage of the customer journey. They're excellent at diagnosis.

What they don't give you is the work design—the operational layer that makes the framework actually function:

→ Who does the work at each stage?

→ What are the explicit transition criteria between stages?

→ What information transfers at each handoff?

→ What does "ready" look like before work moves forward?

→ What's the daily and weekly rhythm that surfaces problems before they compound?

This isn't a criticism of those consultants. They're teaching what they know. Their backgrounds are in strategy, marketing, and revenue—not in workflow design, handoff protocols, or operational systems.

But the result is the same pattern Graham identified in 2013: founders end up with beautiful frameworks and chaotic execution. Strategy is clear, but every deal, every project, every client engagement is handled differently depending on who's doing it.

The Missing Layer

This is the problem Deliberate Work was built to solve.

Not to replace your GTM framework—those are useful. Not to tell you your strategy is wrong—it probably isn't. But to provide the operational architecture underneath whatever framework you're using.

Deliberate Work operates at the atomic level:

GTM Frameworks Tell You

The stages.

Awareness → Acquisition → Activation → Engagement → Retention → Revenue → Referral

Deliberate Work Tells You

The work at each stage.

Who does what, when, with what inputs, producing what outputs, triggering what next step.

When you design work deliberately from the start, something powerful happens: every unscalable thing you do becomes a draft of your eventual system. You're not just learning—you're building the scaffolding that will hold your learning.

The manual customer onboarding you're doing today? It's not just "getting the customer set up." It's also revealing exactly what your onboarding workflow needs to include—the steps, the handoffs, the information requirements, the success criteria.

The difference is whether you capture that as you go, or hope you remember it later.

The New Rule

Paul Graham's advice doesn't need to be replaced. It needs to be completed.

"Do things that don't scale" was the right answer to the wrong question. The question founders were asking was: "How do I get this off the ground?" And the answer—do the hands-on, high-touch, unscalable work—was exactly right.

But the better question was always: "How do I get this off the ground in a way that I can eventually hand off?"

And for that question, there's a different answer:

Do things that don't scale—but do them deliberately.

Let the unscalable work teach you what your system needs to be. Then build the system as you learn, not after.

The hands-on work is still essential. You still need to recruit users manually, go overboard on service, and handle things by hand. That's where the learning happens.

But now you can do that work inside a framework designed for scale. You're not waiting until you have scale problems to design the system. You're building the system while you're still small enough to get it right.

That's what deliberate means. Not slow. Not over-planned. Not "corporate." Just intentional about capturing what you learn in a form that compounds.

Starting Now

If you're doing unscalable things right now—and you should be—here's how to do them deliberately:

- 1 Every time you do something manually, ask: "What would this need to look like if someone else were doing it?" Write down the answer—even a rough draft.

- 2 Every time you make a judgment call, ask: "What information did I use to make this decision?" That's the beginning of a decision rule.

- 3 Every time you handle an edge case, ask: "Is this a one-off, or will this happen again?" If it'll happen again, document how you handled it.

- 4 Every time work moves between people or stages, ask: "What needs to be true before this handoff happens?" That's a transition criterion.

- 5 Every time something goes wrong, ask: "Where in the workflow did this break?" Not "who dropped the ball"—"where." That's a system problem, not a people problem.

None of this slows you down. It takes seconds per instance. But compounded over weeks and months, you're building something most founders never build: an operating system that actually reflects how your business works.

You're doing things that don't scale. But you're doing them deliberately. And when it's time to scale, you won't be excavating—you'll be extending.

The Choice

You're going to do unscalable things either way. There's no shortcut through the early-stage work. The high-touch, hands-on, figure-it-out phase is real, and it's necessary.

The only question is what you'll have to show for it when you come out the other side.

One path leads to chaos that scales—workarounds baked in, tribal knowledge scattered across people's heads, every new hire requiring months of "learning how we do things here."

The other path leads to a system that scales—designed from the work itself, capturing the learning as it happens, ready to extend because it was built to.

Same work. Different outcome.

Paul Graham was right: do things that don't scale. But do them deliberately—and capture what you learn in a form that does.

Sources & Further Reading

- Paul Graham's original essay: Graham, P. (2013). "Do Things That Don't Scale." paulgraham.com.

- On the "Collison installation": The Stripe founders' technique of setting up customers on the spot became legendary in Y Combinator circles as a model of hands-on, unscalable customer acquisition.

- On scaling operations: The challenge of transitioning from founder-driven to system-driven operations is well-documented. See also: How to Start a Business Deliberately.